Centralisation and decentralisation: a conceptual walk-through

In Part 1 I offered a non-technical overview of blockchain technology and its relationship to the writings of Hayek on money and monetary systems. It was argued that there is not only good reason to view his proposal for a denationalised monetary system free from centralised government control as prefiguring the most well-known example of blockchain technology, the cryptocurrency bitcoin. We also saw that Hayek’s concern with the political obstacles to the adoption of such a system would most likely be faced by bitcoin as a new form of money. Hayek appears to be a pioneer of cryptocurrency avant la lettre.

Yet, whilst certainly notable, Hayek’s place in the history of cryptocurrency and Web3 is not as straightforward as all of this suggests. It turns out that there is a fundamental difference between the Austrian’s idea of monetary denationalisation and that of bitcoin, and indeed between the notion of decentralisation upon which his proposal is based and the structure of the blockchain networks upon which Web3 more generally is built.

To illustrate the difference, and to commence our journey into the philosophy, politics, and economics of Web3, let us imagine a configuration of dots that represent a group of people who require a service. For now, it does not matter how many people are in the group, nor which service is required:

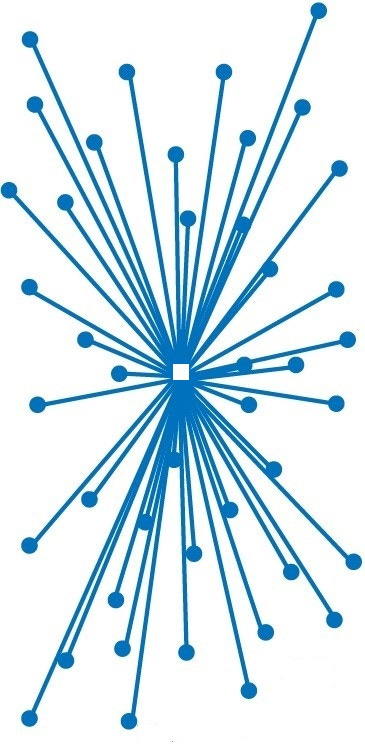

First, note that the way in which we connect the dots allows us to represent the difference between centralised and decentralised governance structures. In the first our group of people (hereafter, our “clients”, or “customers”) would be dependent upon the decisions of a single point, or “node”, of decision-making authority. Without being concerned with the very different philosophical question of how the central node has acquired this authority, and whether it has done so legitimately, we can represent that relationship within the structure by placing a square at the centre of our diagram:

Here it is the central node that decides how the service is best provided, and what the terms of service should be. In other words, and independently of how it has assumed this authority, the central node is a “rule-maker”, whilst each of the clients is a “rule-taker.”

As we saw in Part 1, a governance structure configured in this way may paradoxically be both too powerful and too vulnerable. Too powerful because it bestows too much power upon the authority that oversees it, and yet too vulnerable because precisely in doing so it presents a significant risk to those who are dependent upon it for delivery of the service. A single node of centralised authority, we will recall, can also become a single point of failure. Moreover, and precisely because of their centralised mode of governance, such structures run the risk of operating on a “like it, or lump it” service provision ethic. In other words, and precisely because of the absence of alternative modes of provision within them, we may say that centralised governance structures are systemically risky because they are monopolistic by design.1

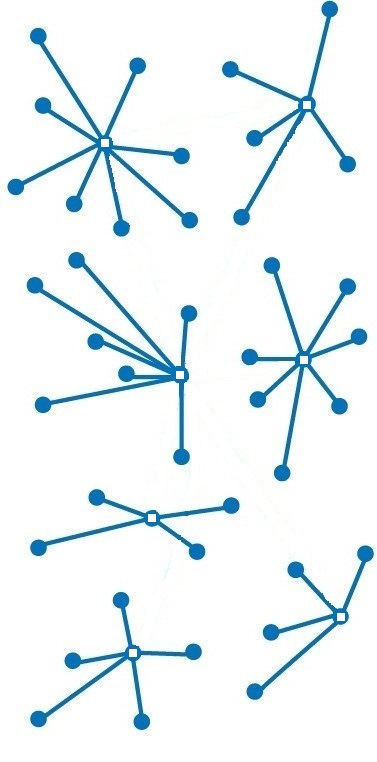

As a remedy we could replace the centralised network with a decentralised or federated one. Here decision-making authority is devolved away from a single node to multiple nodes operating under a common set of rules. Note also that neither the number of clients nor their position in the diagram, have changed (even those newly elevated to positions of decision authority are still recipients of the service). Rather, all that has changed is the way the clients relate to authority:

How, then, may this governance structure be an improvement over its centralised alternative?

Decentralisation addresses the problem of power, it is argued, by distributing decision authority within the structure across multiple providers, rather than concentrating it in one. Similarly, the problem of the single point of failure is addressed by limiting the contagion effects of poor decision-making to only those clients who are in receipt of a poorly functioning provider’s services.

Of course, whilst possibly an improvement upon centralised governance structures, and as socialist anarchists have long pointed out, decentralised structures end up begging the questions that the power and single-point-of-failure problems raise with respect to the individual nodes of authority within them.2 How often do we hear of clients complaining about unresponsive customer services departments, of invidious terms of business or of employment, or of outrageous CEO bonuses and severance packages? This notwithstanding, and whilst even in decentralised structures clients are typically not permitted a direct say on how the individual nodes of authority within them are run - they are still rule-takers - they do have an indirect say by being permitted to switch from one provider to another in the quest for better terms of service. We could say, then, that an important difference between centralised and decentralised governance structures is that “like it, or lump it” is replaced with “see if you can do better next door,” the effect of which is that each individual node of centralised authority is incentivised to improve best practice to maintain market share.

Rethinking decentralisation

It is at this juncture where matters become interesting from a conceptual standpoint. Until the advent of blockchain technology